Software ate the world; what's AI going to do to software?

Under the hood, the AI era can be understood as the migration of users from producer-published software to platform-published software. The specifics of how that happens have massive implications for our everyday lives.

These predictions are built on the stipulation that users will increasingly make AI platforms an indispensable part of their daily lives. It’s completely valid to reject that premise, I just want to be forthcoming about what assumptions I’ve baked into this essay.

Software publication via platforms

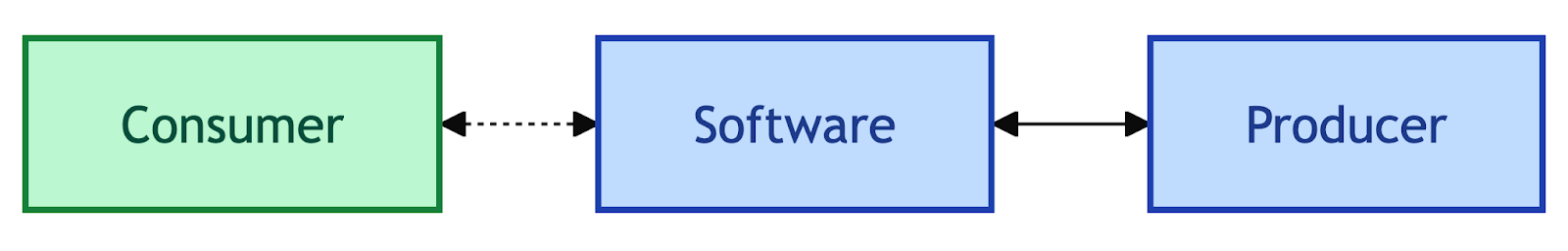

On the internet, consumers use software to transact with producers. That software is typically developed and published by the producers. And that software is designed to serve the interests of the producer. TikTok wants you to watch more videos (see more ads). Indeed wants you to apply for more jobs. DoorDash wants to bundle shaving cream from CVS along with the burrito that Chipotle’s making you. They’ll develop their software accordingly.

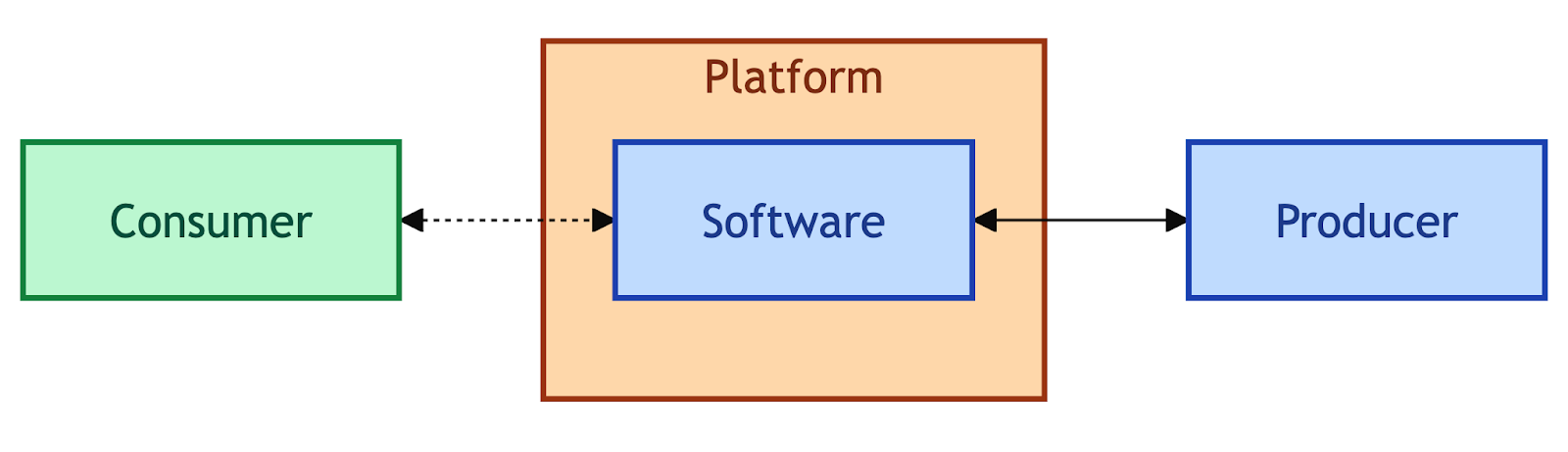

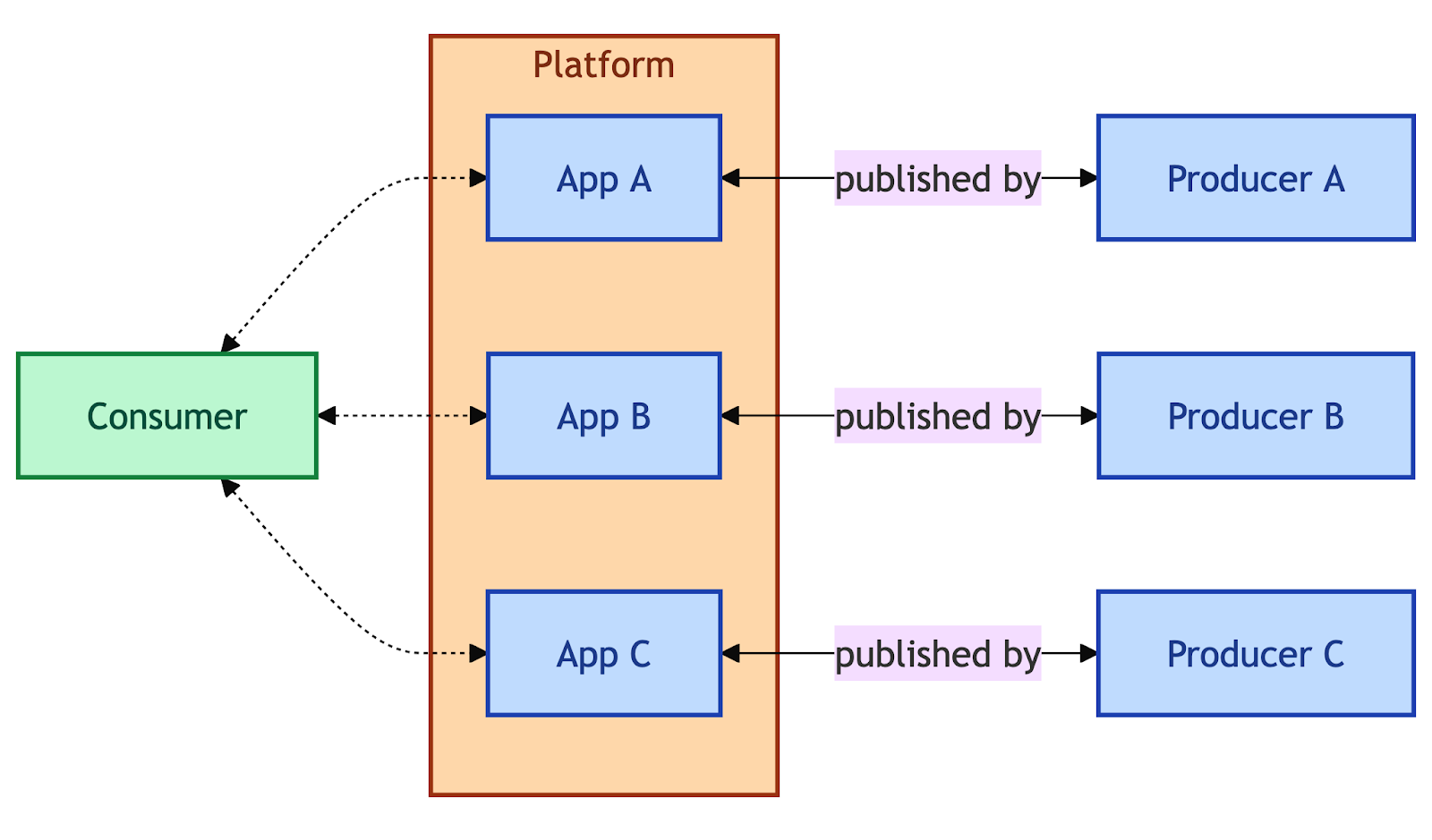

But software is rarely distributed by the producer. It’s downloaded by the user through a platform. Today’s dominant software platforms are the web and app stores. The producer distributes their software by making it available - publishing it - to a place where consumers can find it. The web’s constraints on users and publishers are largely technical and generally not economic - there’s no de jure rent-seeking entity there. App stores, though, are a different beast. We’ll get into that in a moment. But let’s update our diagram:

Post-iPhone, when Steve Jobs and Tim Apple saw that diagram their pupils turned into dollar signs. They correctly predicted that the platform could be a source of incredible leverage given a critical mass of users, which they brought to bear with spectacular results. Unfortunately for the Apple folks, there’s a limit to that power. Apple publishes only a relative handful of apps themselves, which puts them partially at the mercy of publishers/producers. If they alienate the producers, the value of the platform goes down. Let’s draw a rectangle in our diagram to illustrate. Look at all those blue boxes that can gang up on Big Orange:

The enshittification quotient

Call that the enshittification quotient: the maximum extent to which a platform can capture value from transactions between consumers and producers therein. The web has an enshittification quotient that approaches zero, though user tracking/ad tech are a really interesting side quest that I won’t go into because they’re not inherently a part of the platform. App stores have a much higher enshittification quotient. There are a ton of other examples out there, but I want to remain laser-focused on software distribution because I think that’s where persons of conscience should focus.

There’s a new type of platform emerging, though, and that’s the AI Agent. I’m sure you’ve heard of it. If you’re in Control-F mode, I’ll also call this ChatGPT, Chatbots, AI assistants, LLMs, agentic experiences, and so on. I’ll be grateful for one authoritative collective noun to describe this type of thing. These platforms have a unique capability: they can generate and execute code. That makes all the difference in the world because it means the platform has no theoretical limit on how much software it can publish. The enshittification quotient for an AI Agent platform is unknown; it has no theoretical ceiling but could be bounded by certain market conditions. We’re early enough in the process that there’s considerable opportunity to limit the damage.

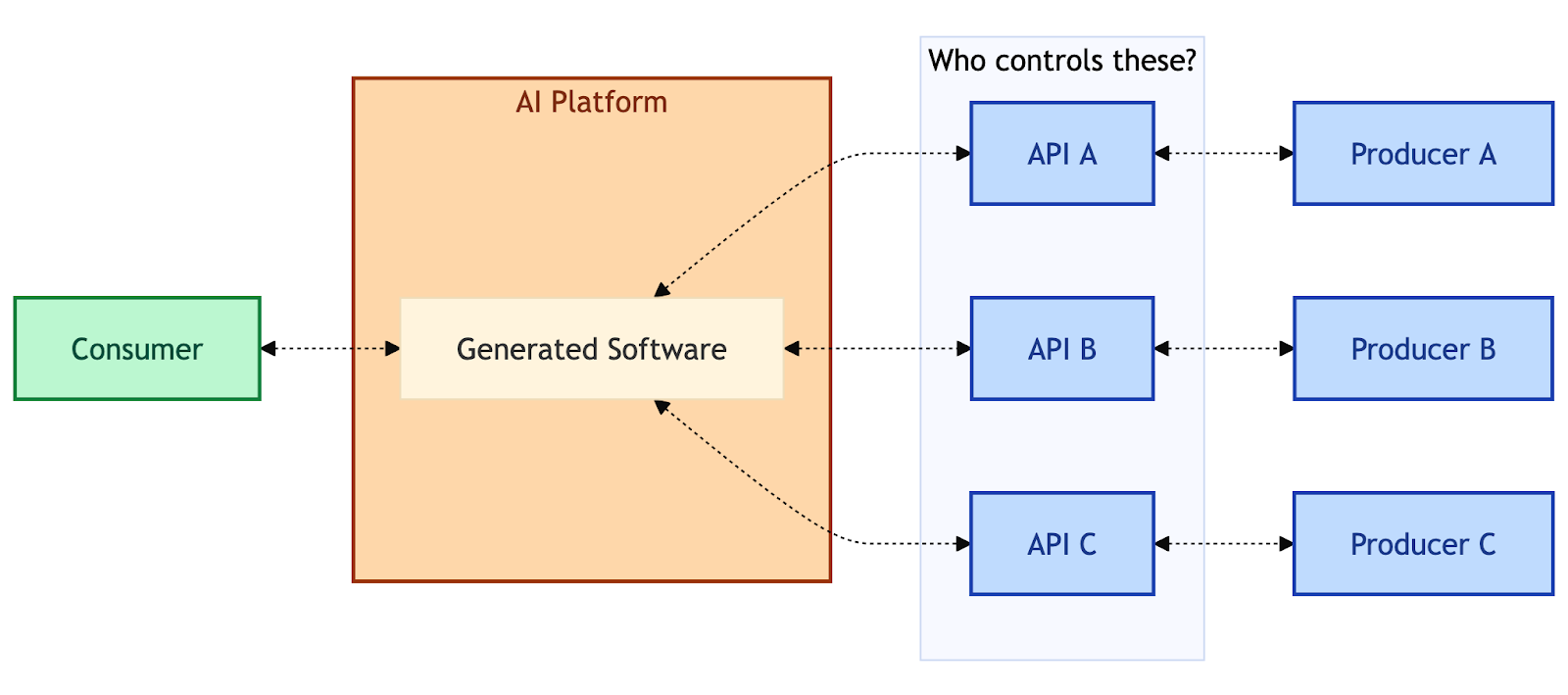

Using a fictionalized AI Agent that exists in the very near future, let’s buy a rug. Prompt: “I want a 5x8 rug in a geometric pattern, mostly earth tones.” What do we see? The AI Agent platform can’t design, fabricate, and ship a rug right there (though that’s an interesting rabbit hole to go down) - they’ll need to connect the consumer’s prompt to a plausible match from a producer. It’ll probably respond with a few rectangular cards containing some rug choices. For simplicity’s sake, let’s say I like the second one, which shows a little icon that indicates that it’s from Target, and a price of $99.99. Prompt: “The second one.” Response: “Great. I’ll place that order now.” I get notified when the transaction completes and later when it ships. Cool. Where will AI Agent Platform, Inc. get the right to show Target’s inventory and branding in their experience? That’s the key question. It turns out, there’s another layer (APIs) in our diagram:

Today, the producers’ data and capabilities are largely coupled with the software applications they publish. Their house, their rules. But when software distribution becomes a property of AI platforms, it’s possible (though not a foregone conclusion) that data/transactions could follow suit, at least to some extent. One thing is clear to me, though: AI Platforms will not make money from providing LLMs as a service in the foreseeable future unless the underlying tech gets orders of magnitude more efficient. But if the hosted LLM side of the business is a loss leader in the pursuit of a dominant platform that encompasses both the software and the underlying data transactions, that’s a much more compelling business idea. The rent-seeking potential of such a platform scares me on behalf of consumers and producers. The entire supply chain could be verticalized; imagine Amazon’s dominance in cloud, retail, and logistics but also with a ubiquitous software creation and distribution platform stapled on. Enshittification quotient = infinity.

Predictions in the platform-published software era

With the caveat that antitrust law (will that exist in ten years?) could prevent some of the worst excesses of such a scenario, what conclusions can we draw from this hypothetical example? Here’s my take:

1. In the “gold rush” analogy, AI isn’t the gold, it’s the shovel

Data is the gold. The hype cycle around AI makes it tempting to treat the models themselves as the prize. They’re not. Models are infrastructure: the picks and shovels of this era. They are necessary to participate, but they’re not where the lasting value accrues. What matters is not who has the fanciest shovel, but who owns the gold mine. In the AI context, the “mine” is the data and transaction layer: the flows of inventory, prices, user intents, and completed exchanges that feed the real economy. Whoever controls that registry will have enduring leverage.

2. AI wrappers (aka agentic development) won’t last long

Many companies are now building “agentic experiences”: thin wrappers around foundation models, dressed up with a prompt template and a UI. These are useful as an extension of the producer-published software model, but I don’t believe they have a durable future because they’re structurally misaligned with both consumer behavior and platform economics.

Consumers won’t want to jump from app to app to ask slightly different AI agents to do the same things given a compelling alternative (again, I’m assuming that consumers will increasingly adopt AI platforms). Nobody will open their travel app to type “reserve three nights at the Doubletree in Toronto” into a worse version of ChatGPT, then switch over to the retail app to tell a nerfed Claude they need a new nightstand. That future looks absurd. Consumers put their food orders into DoorDash rather than juggling a dozen restaurant sites, and they will consolidate their various transactions into a handful of dominant AI platforms that can mediate across domains.

From the producer side, the incentives to invest in standalone applications will wane. Maintaining a full-stack app, whether it’s a traditional UI or an agentic experience, is expensive and offers diminishing returns if consumers are defaulting to agents. Web and mobile app development won’t disappear; they’re here to stay. But if the dominant channel for discovery and transaction is an AI platform, producers will pour their energy into making sure their inventory, pricing, and services are optimized for that platform’s data and transaction conventions. Application development becomes less about bespoke consumer software and more about maintaining a compliant, performant data interface.

The same logic applies to chatbots. For the last decade, companies have been coaxed into building their own “assistant experiences” inside apps and websites. These efforts rarely delighted customers, and in an agent-dominated world they will make even less sense. Why build and maintain a second-rate chatbot if consumers can get a first-rate one that already knows their order history, payment methods, and preferences? One-off chatbots will survive only in tightly scoped niches, not as a general strategy for consumer engagement.

In short: the application layer itself is shrinking. Producers won’t stop investing in digital presence altogether, but the locus of value shifts from publishing and owning a bespoke app to participating in and hedging against the platform’s publishing layer.

3. Producers stand to lose a lot of value

When producers no longer publish their own software, they risk being reduced to interchangeable data sources inside someone else’s platform. That shift strips away the direct brand presence (the Starbucks app, the Delta notifications, the Netflix interface) and replaces it with a widget in an agent’s results. Producers become dependent on the ranking algorithms and monetization policies of the platform, just as Amazon sellers live or die by search placement. Margins compress, competition is reframed around who can satisfy the platform’s incentives, and the producer’s relationship with its customer becomes mediated, if not severed. This is the most immediate danger of the platform-as-publisher economy: the alienation of producers from their services.

4. Everyday people will suffer if AI platforms become buyer and seller agents

For consumers, the story is no brighter.

United States v. Google LLC was adjudicated against Google for monopolizing the search engine and search advertising markets, most notably on Android devices, as well as with Apple and mobile carriers. The gist of this case is that Google’s ad marketplace represented the platform, buyers, and sellers. They used the inherent leverage of that position and its (bought and paid for) dominance in the web and mobile markets to cement its dominance. The harm to users was and continues to be evident. Had any of those parties (platform, buyer, seller) been represented by an adversarial organization, the competitive pressure would have made a huge difference in mitigating the moral hazard and distributing more value to the stakeholders in the resulting system.

The lesson? When platforms act as publishers, they gain the power to arbitrate not just discovery, but also the terms of engagement: which products are surfaced, how prices are presented, what add-ons are bundled. More of the economic surplus shifts toward arbitrage and rent-seeking instead of value creation. Consumers face higher prices, less transparency, and less choice. The governance of these platforms will likely be opaque, algorithmic, and unaccountable. So if the trajectory of past platforms is any guide, enshittification is a feature not a bug, and everyday people are the ones who pay.

Our role as tech people

To summarize: the AI era can be broadly understood as the unbounded expansion of software publication by dominant platforms. That collapse could drive user hostility to an intolerable extent if it also encompasses the data transactions that have been traditionally coupled with producer-published applications. Unless producers retain leverage over that all-important data layer, they will be reduced to line items in someone else’s prompt response.

Remember: enshittification is not a general term that refers to software getting progressively worse. It’s a specific tendency of big platforms described by Doctorow: (1) gain a critical mass of consumers by offering value at a loss; (2) attract a critical mass of producers by brokering consumer data and engagement, still at a loss; (3) incrementally and progressively exploit both tenants once the cost of switching becomes sufficiently high. We are currently in phase 1: AI products are being jammed down our throats left and right, often at low or no cost to the consumer. The unit economics are awful for the platform until they reach phase 3, and I am convinced that phase 2 (and therefore, 3) can be prevented, though I don’t know how.

All I can offer is a challenge to the tech industry: our opportunity and the urgent calling of this era is to build the technical and economic infrastructure to ensure that AI platforms cannot double- or triple-deal between consumers, producers, and themselves. The consequence of failure are dire.

Keep the conversation going

I really appreciate feedback from anyone and everyone who reads my posts, so please feel free to say hi at @jeff.auriemma.xyz and keep the conversation going.