I want Artificial Competence, not more Artificial Intelligence

A person contacted an airline’s customer support chatbot after a family death. They wanted to know whether they qualified for a bereavement fare. The bot told them yes, and explained that they could book a regular ticket and apply for the discounted rate afterward. They followed the instructions. The airline later refused to honor the discount. The case ended up in front of a tribunal, which ruled that the airline was responsible for the information its AI system provided and had to pay the difference.

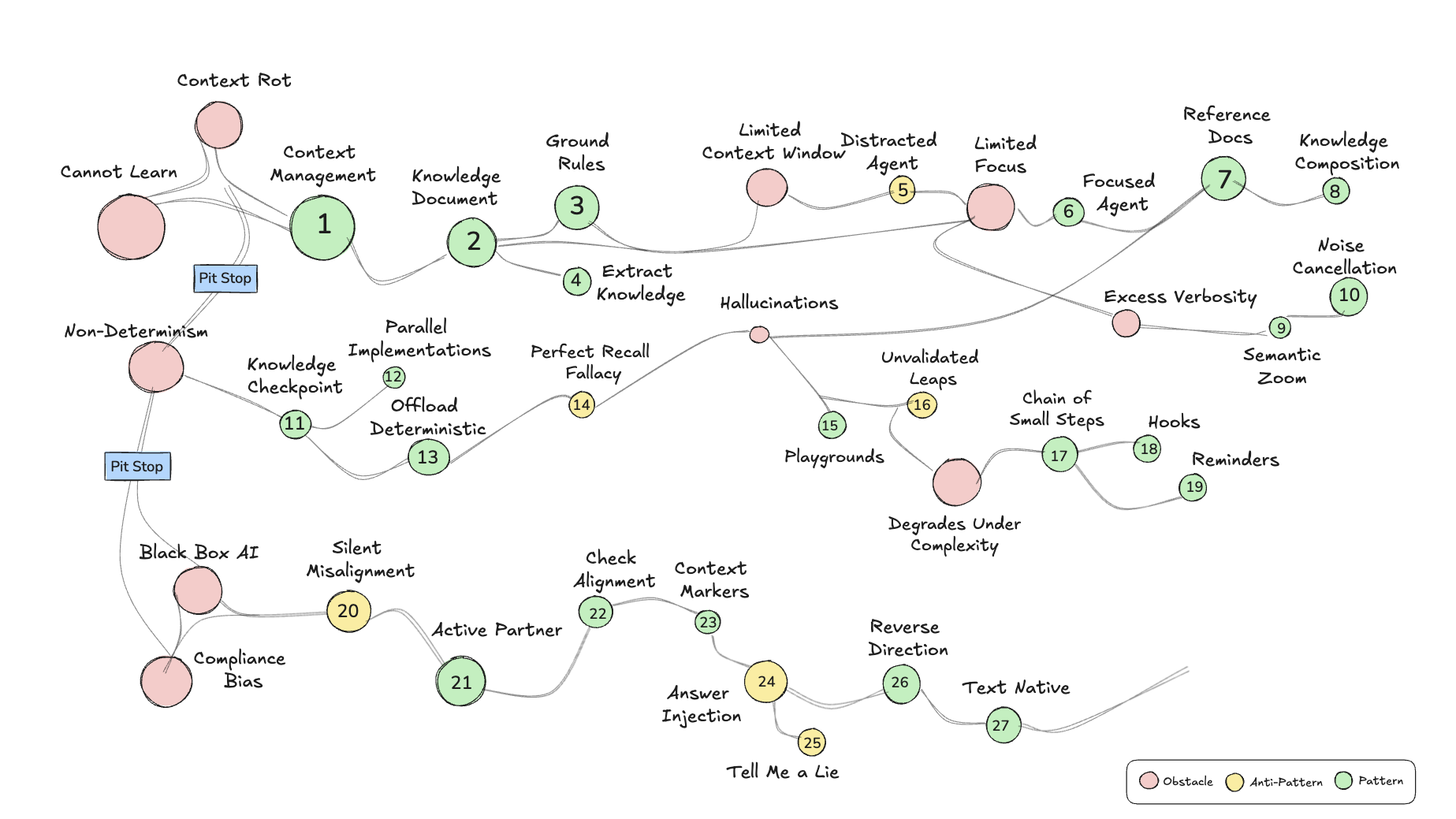

That case, Moffatt v. Air Canada, is the first high-profile commercial example I’m aware of that showcased the hazards posed by improper usage of LLMs. We have clever names for the workarounds that have emerged to prevent these scenarios: context management, prompt engineering, fine tuning, and so forth. One of my favorite tech talks on this subject was given by Lada Kesseler. The talk expertly guides the listener through a map of obstacles, patterns, and anti-patterns that one encounters when using agentic coding tools. I remain bewildered by this map, not just by its exhaustiveness and utility but by the fact that it has to exist at all.

The pithy way to put it is that we are trying to engineer consistency and reliability into systems that are, by design, inconsistent and unreliable. Since consistency and reliability are the hallmarks of competence, the even-pithier version is that we are practicing Competence Engineering.

Kesseler’s talk gives shape to this emerging domain. I like her work as much as I dislike the need for it. (A lot.) As a former pro musician, I am deeply familiar with the “genius who can’t show up to the gig on time” type of individual. They are exhausting and beautiful in equal parts. I would listen to their music all day if I could, but they’re terrible bandmates. I’d have to call them the day before the show. And an hour before they were supposed to leave to get to rehearsal on time. The constant babysitting is a sap on attention and motivation. When I look at Kesseler’s diagram, I get flashbacks to how I had to manage “Josh” (pseudonym to protect the “innocent”).

I put up with Josh because I thought he was worth it, on balance. And we (engineers? White-collar workers? People in general?) are hypothesizing that investing in these emerging disciplines is worth it because the payoff can be so big. LLMs can reduce toil and expose capabilities that were previously out of reach or unfathomable.

But I worry that “we” are losing track of a bigger prize: reducing and eventually eliminating the need for this sort of micromanagement. Yes, I put up with Josh, and I put up with LLMs, because they’re awesome. But I fully expect the Putting-Up-With-It Era to pass, lest our professional lives be forever dominated by incremental Competence Engineering improvements. The real revolution will be the conquest of Quadrant 3.

What is Quadrant 3, you ask? To that I’ll invoke another person whose work I admire and will complain about: Dwight D. Eisenhower. His Matrix haunts me:

I am pleased to say that, like many workers, I’m pretty good at Quadrants 1, 2, and 4. I am in search of “The Delegation Zone,” the entity to which I can readily delegate those pressing and unimportant tasks. I cannot understate the impact that having a reliable Quadrant 3 offload would have on ordinary people’s lives (Eisenhower, I assume, had enough people to do Quadrant 3 work). The ability to take low-level-but-not-optional things off our plates would put countless hours back in the hands of people so they can cook, paint, spend time with family/friends, sleep… the good stuff.

I am tantalized by the possibility that agents could be our Quadrant 3. Every now and then I do a little experiment and always walk away disappointed. When I consider this in the context of Kesseler’s diagram, it’s not surprising. Fully realizing the productivity gains promised by AI tooling requires a lot of expertise to bring to bear.

So what am I to make of an entity that’s sold as having “PhD-level intelligence” that can’t be trusted to correctly order a burrito or manage a calendar or follow the system prompt?

Sure, it’s great that it can do data entry, turn Shakespeare into almost-workable rap lyrics, write a Perl one-liner, and suggest a passable marathon training plan in the same minute. But that doesn’t really help most people live their lives better. AI boosters insist that real autonomy is just around the corner, but all I see are a bunch of Joshes. I’m willing to keep investing the time to learn how to use these tools well. But agents remain constrained by fundamental limitations in today’s frontier models, and that’s disappointing. I don’t want a thousand more Joshes. I don’t want more elaborate schemes for managing them. I want tools that show up on time. Artificial Competence can’t come soon enough.

Keep the conversation going

I really appreciate feedback from anyone and everyone who reads my posts, so please feel free to say hi at @jeff.auriemma.xyz and keep the conversation going.