You're all staff engineers now

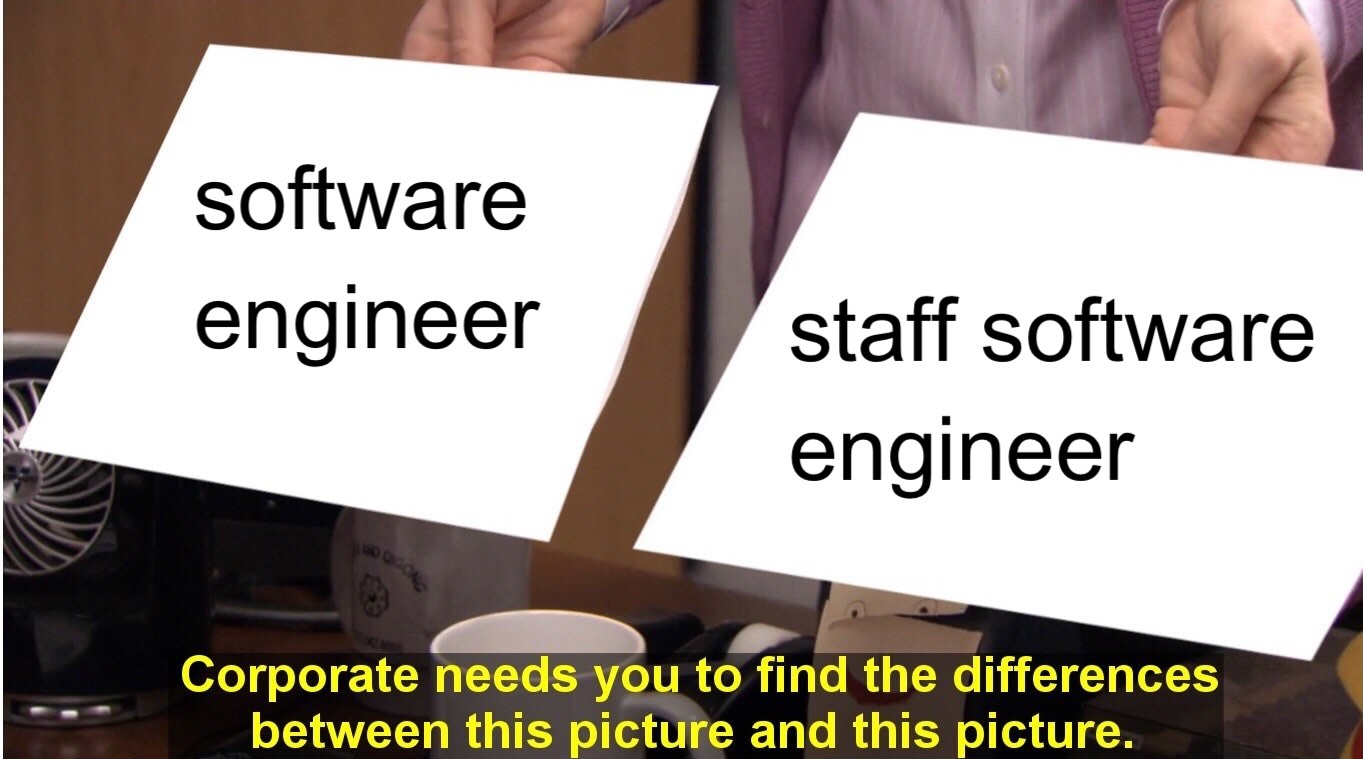

Don’t get excited, I’m not promoting you. I’m simply pointing out that the craft of software engineering is changing rapidly and managers are going to adjust expectations accordingly. This isn’t some AI-pilled cheerleading perspective, by the way; but I think most fair-minded people can agree that code has become cheaper to produce over the past year or so. This comes on the heels of a much more modest revolution: the rise of the staff engineer.

Let’s start there. One of my favorite software books is Tanya Reilly’s The Staff Engineer’s Path. It’s an indispensable resource for individual contributors and engineering managers like me. Here’s the passage I want to highlight: “Early in your career, if you do a great job on something that turns out to be unnecessary, you’ve still done a great job. At the staff engineer level, everything you do has a high opportunity cost, so your work needs to be important.” For many engineers, from intern to senior, the “something” you do a “great job on” is primarily writing code. Sure, there is a sliding scale of expertise when it comes to implementation, estimation, testing, scope, and planning sophistication but you get the drift. When production code is written by hand, the cost of “getting it wrong” is relatively high, so the difference between success and failure is very tangible to management and we are able to articulate what progression and achievement looks like with a fair bit of precision.

Once they achieve senior level, it becomes clear that some engineers possess uncommon and valuable domain, technical, and/or executive skills. These skills are distinct enough to merit further advancement. Recent consensus deems this “staff” level engineering. Reilly proposes a taxonomy of these skill sets in the Tech Lead, the Architect, and the Solver. The Tech Lead partners closely with a manager (or teams of managers) to guide execution. The Architect is responsible for technical direction (and often technical quality) across a large domain or technology area. The Solver tackles particularly difficult, high-leverage, high-ambiguity problems. These may be urgent crises, deep technical debt, unknowns, cross-team coordination problems, or strategic obstacles.

To quote myself from a couple paragraphs ago:

When production code is written by hand, the cost of "getting it wrong" is relatively high

Considering that I mentioned AI earlier, you probably can guess where this is going: the cost of “getting it wrong” is going down. Production code is increasingly not being written by hand; LLM-powered tools are generating more of it. The exact numbers are fuzzy because foundation model providers, tech executives, and VCs are incentivized to make their usage stats seem as impressive as possible. Based on those faulty stats and anecdata from my experience, I’m confident in saying that the trend line is going up, which means that (re-)writing code is becoming cheaper. Spamming Claude Code to brute-force an implementation to correctness becomes a compelling alternative to relying on developers’ judgment. That sort of implementation work has traditionally been the crucible of the software engineer’s skill set. We in engineering leadership must reckon with the great decoupling of writing code from career progression.

I’ll quote myself quoting Reilly from a couple paragraphs ago:

"At the staff engineer level, everything you do has a high opportunity cost, so your work needs to be important." - Tanya Reilly

I don’t think Reilly was implying that other work was objectively not important, it’s just that certain tasks like all-day-coding were not typically the best use of time for engineers at or above the staff level. But Reilly wrote her book before the rise of agentic coding. Given all that’s changed, it’s plausible for management to conclude that non-staff-shaped work is actually unimportant. That terrifies me because there are a ton of influential people in the tech world who would love nothing more than to cut the rungs off the career ladder and lay off as many software engineers as possible. That’s a terrible idea, both ethically and practically. Software engineering is a necessary craft and cutting off its source of talent is foolhardy. So, what’s the alternative to “everyone’s fired?” to a conscientious manager? It’s simpler than you might think:

Everyone’s a staff engineer now. If those are the folks doing important work, then that’s what all software engineers all must become. It’s absurd, I know. Staff engineers aren’t created by fiat, they’re forged in the fires of Mt. Doom too many trips through the SDLC. They’re special jewels tucked away in the caves of normie developers, a 10x treasure to be plucked from obscurity by enlightened directors and vice presidents of engineering. And yet, we must change, because times have changed. Look no further than the daily rituals of software engineering: the standups, the reviews, the syncs. They may be morphing into coordination layers for semi-autonomous agents. If you’re orchestrating between a handful of humans and a handful of models, deciding who gets to make what decision, you’re doing the job of a staff engineer. In this context you’re not managing people so much as managing epistemology: whose output counts as truth and under what conditions. Of course, the scale and scope of impact matters, so I’ll propose a thought experiment.

Suspend disbelief for a moment and imagine what the day-to-day life of a Junior Staff Engineer would be. In my mind, it’s almost an apprenticeship. They’d work closely with their more senior counterparts to cultivate the skill sets associated with Reilly’s archetypes. They would coordinate AI and human workflows like a Tech Lead. They would vet the coherence and sustainability of ensuring model-generated systems like an Architect. They would triage and diagnose emergent failures of AI-assisted production code like a Solver. And they’d also be cultivating the craft of context engineering/prompt engineering/tool orchestration (pick your buzzword). Their progression would be facilitated not just through person-to-person mentorship but also a thoughtful curriculum of software architecture best practices, learning to see the forest without having to mind the trees as much. A Junior (or some other early-career title) Staff Engineer would still code by hand where appropriate but like their higher-level counterparts, they’d need to be selective about what tasks need their hands-on attention.

If this all sounds hand-wavey to you, that’s because it is. Anyone who acts like they know what they’re doing and where they’re going in this era of software engineering invites suspicion. I will go out on a limb and say that I think my diagnosis—that software engineering career progression needs to be rethought in this era—is something I stand by. “Oops, all staff engineers!” may not be the right prescription, though. But it’s valuable as a provocative conversation-starter, so I humbly present it to you.

Keep the conversation going

I really appreciate feedback from anyone and everyone who reads my posts, so please feel free to say hi at @jeff.auriemma.xyz and keep the conversation going.